If you hadn’t heard, August is Biosecurity Awareness Month. Senior Consultant at MartinJenkins Jess Ashley reminds us how critical biosecurity is for our economy, and she shares lessons from some of our firm’s work in this area.

The reputation of Aotearoa as a clean, green producer of high-quality food and fibre products rests on something most New Zealanders rarely think about – our world-class biosecurity system. But it’s something government and industry are always thinking about a lot – for instance, “World-class biosecurity” has been ranked as the top priority for the agribusiness sector for the 15th year running, according to the KPMG Agribusiness Agenda.

A range of emerging and potential pests and diseases keep our Biosecurity New Zealand people up at night. These pose significant risks to our crops, livestock, native ecosystems, and marine environments, and they could have devastating effects on our economy.

“…. they will eat anything they can find …”

Our biosecurity measures must be sturdy enough to address threats from both land and sea. Terrestrial pests such as insects and plant diseases threaten our land-based agriculture and forestry sectors. The brown marmorated stink bug, for example (the one staring at you at the top of this article), hitchhikes on passengers and imported goods. It feeds on more than 300 plant species and, if established in New Zealand, could decimate our fruit and vegetable industries.

Marine pests like invasive seaweeds and marine organisms can disrupt our aquaculture and fisheries industries. For example, the Northern Pacific seastar poses a huge risk to our native biodiversity. It can hitchhike on boat hulls coming into the country, and larvae can be drawn into a vessel’s ballast water. It can also settle on mussel lines and salmon cages, and so cause serious damage to our aquaculture industry. Biosecurity NZ describes this sea star as “an eating machine …. they will eat anything they can find, like dead fish and even each other”.

It’s hard to overstate what’s at stake for Aotearoa

Our primary industries generated nearly $60 billion in export revenue this year, making up over 80% of our total exported goods. These industries, spanning agriculture, horticulture, forestry, and seafood, also support hundreds of thousands of jobs across the country.

This success is built not only on New Zealand’s reputation and the sector’s resilience, but also the strength of a biosecurity system that has kept devastating pests and diseases at bay.

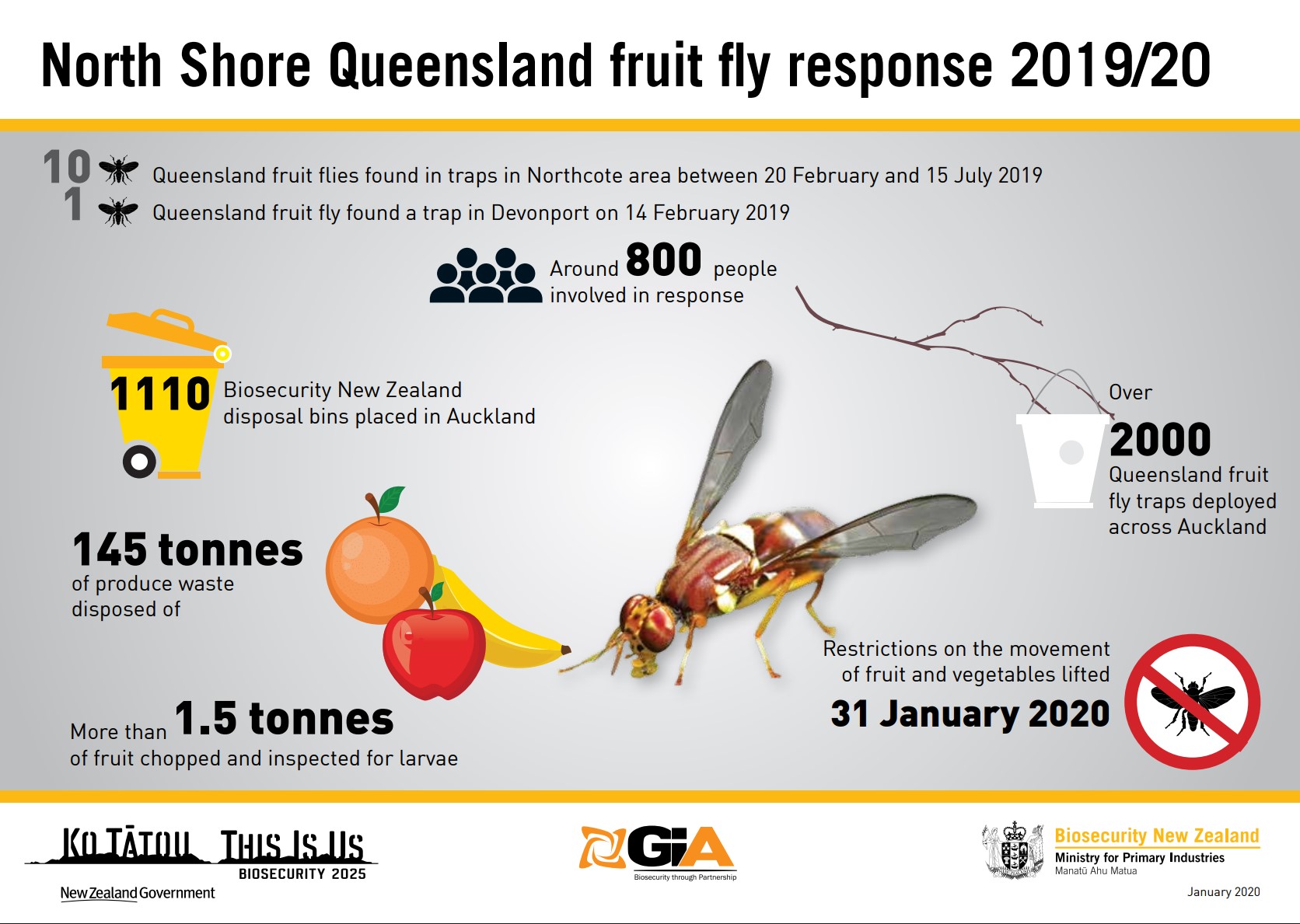

Consider the Queensland fruit fly – a pest we've successfully intercepted and eradicated multiple times. If it were to establish itself permanently here, the economic impact on our $7 billion horticulture industry alone would be catastrophic.

The stakes are even higher for livestock diseases. If foot and mouth disease were ever detected in New Zealand, it would shut down all meat and dairy exports immediately and put our hard-won trade relationships at risk. Economic modelling by NZIER suggests the impacts from a foot and mouth outbreak would ripple through our economy for years, affecting not just farmers but also processors, transporters, and countless rural businesses that rely on a functioning, disease-free supply chain.

It’s not just agriculture and our other food and fibre industries

While primary industries often grab the headlines, biosecurity threats reach far beyond farms and forests.

Tourism now contributes more than $44 billion annually to New Zealand’s economy, including nearly $17 billion from international visitors, and it relies heavily on our clean, green image. A major biosecurity failure could severely damage that reputation and undermine one of our most valuable export sectors for years to come – a threat that my colleague Sarah Baddeley discussed recently in her article on how government, our tourism industry, and communities can shape our tourism recovery.

Recently, for example, the spread of kauri dieback disease has led to track closures in popular parks, directly affecting conservation efforts and the local tourism economy – especially in regions that depend on recreational visitors.

Our cities aren’t immune either. The painted apple moth outbreak in Auckland in the early 2000s triggered a costly aerial spraying programme, showing how invasive pests can disrupt city life and affect property values.

Biosecurity is a vital but mostly invisible infrastructure of success

What makes New Zealand's biosecurity system remarkable is how invisible it is when working well. Every day, biosecurity officers are inspecting and screening countless containers and mail items and managing surveillance networks across the country. This invisible infrastructure is as critical to our economic success as our ports, roads, and digital networks.

The system's strength lies in its integrated approach. It's not just about border controls – though our strict entry requirements are world-leading. It's about surveillance systems that can detect new incursions early, rapid response capabilities that can eliminate threats before they establish, and long-term management programmes for pests that do become established.

Biosecurity work is getting harder: we need to keep investing and adapting

Climate change and increasing international trade and travel are making biosecurity more challenging than ever. The pathways for pests and diseases to reach New Zealand are multiplying, while climate change is generating potential new threats from species that previously couldn't survive here.

At the same time, the value of the industries that rely on effective biosecurity protection has recently been increasing spectacularly. The Government’s June 2025 “Situation and outlook for primary industries” forecast some big jumps in export revenue for the year to 30 June 2025, including dairy export revenue increasing by 16% to reach a record $27.0 billion and horticulture by 19% to reach $8.5 billion.

All up, food and fibre export revenue was expected to increase by 12% to reach a record $59.9 billion for the 2024/25 year, and then to increase a further 2% in the year to 30 June 2026, to reach $61.4 billion.

Against that background of increasing threats and growing economic stakes, adequate investment in biosecurity protection – both in technology and in people – is going to be crucial for New Zealand to maintain world-class surveillance and response capabilities.

However, the level of spending on biosecurity has remained relatively static. For the 2025/26 financial year, the Minister for Biosecurity is responsible for a total of just over $427 million for Biosecurity: Border and Domestic Biosecurity Risk Management, up just a little more than 2% on the previous year. This funding supports the management of biosecurity risks from trade and travel, as well as responses to incursions, and compensation for affected parties.

This raises questions about whether current funding levels are sufficient to match the scale of the risk and the economic stakes. Biosecurity is fundamentally an investment in New Zealand's economic future, and the economic returns from this investment – measured in preserved export markets, protected ecosystems, and maintained international reputation – are among the highest of any public spending. Every dollar spent on prevention and early response also saves multiple dollars in avoided damage and eradication costs.

It may be time to explore alternative or supplementary revenue sources to ensure the biosecurity system continues to be effective against future threats.

The Caulerpa response shows what a partnership approach can do

As we look ahead, maintaining New Zealand's biosecurity advantage will require continued investment, innovation, and collaboration.

Recent work my firm did with iwi and regional councils on combating the invasive seaweed Caulerpa reinforced for us just how quickly a single invasive species can threaten entire marine ecosystems and the aquaculture, fishing, and tourism industries that depend on them.

But for us, what made this project particularly significant was the strategic partnership that underpinned it. We worked alongside iwi, industry groups, top scientific experts, and representatives from central and local government to develop an indicative business case for what would be required to deliver a step-change in Caulerpa response efforts.

The work demonstrated how effective biosecurity responses require more than just technical solutions – they depend on strong, flexible governance frameworks that enable quick responses to emerging threats, they need to be founded on sustainable funding models, and they also need to get local communities involved. It was a timely reminder that a partnership approach where government, industry, iwi, and communities unite against a common threat is the strongest basis for a response to be effective and enduring.