Sarah Baddeley and EeMun Chen look at how our building and construction apprentices might be better supported to get across the finish line in good shape. This article summarises the findings and recommendations from our firm’s February 2025 research report "Strengthening support for apprenticeships – issues and opportunities", which we prepared for ConCOVE Tūhura.

Earlier this year, our team at MartinJenkins worked with ConCOVE Tūhura – New Zealand’s Centre of Vocational Excellence for the building and construction industry – to help them understand how government-funded support programmes for apprentices are working for employers, training providers, and workers in the industry.

The research came at a good time: the construction sector is experiencing significant changes and financial pressure, and apprenticeships are critical for providing the talented workforce needed to increase the sector’s productivity.

We looked broadly at support for apprentices, including all financial and non-financial supports and measures for attracting people into apprenticeships, training apprentices, and getting them across the finish line. We found there were several areas where the current apprenticeship-support system is facing difficulties.

What we found

Demand is high but completion rates are low, with support programmes prioritising starting over finishing

Construction is New Zealand’s fifth-largest industry, producing just over 6% of our national GDP. Looking beyond the current cyclical contraction, our construction and infrastructure sector is expected to continue seeing high demand for skilled workers. But industry analysis indicates a roughly 50% shortfall in the workforce needed to deliver on the projected building and civil infrastructure pipeline.

The sector has seen steady growth in apprenticeship enrolments over the last decade, with enrolments more than doubling from 2014 to 2023. But completion rates are low, ranging between 39% and 58%. That’s significantly lower than comparable countries like Germany, Ireland, Scotland, and the Netherlands, where completion rates range between 65% and 75%. We also have big variations in completion rates by ethnicity and gender.

Until the recent shift in the Fees Free programme to apply to the final year, the system was almost entirely geared towards participating rather than completing. The system needs to address the key barriers people are facing in trying to finish apprenticeships.

Financial barriers continue to be important

Although apprentices get paid wages, starting rates are usually set at minimum-wage or training-wage levels. The apprentices we interviewed and met with told us they had only been able to take on an apprenticeship because they were living with parents or had a partner to rely on for financial support.

To an extent that’s no different from other students who are also working, but apprenticeships already require a combination of work and study and therefore many of them aren’t in a position to take on a second job to meet their living costs.

This financial pressure is particularly severe for older learners retraining in new careers. Contrary to the popular perception, apprentices are typically older than other tertiary learners and they often have significant financial responsibilities. The mean age range for university learners is 20 to 24 years, but for institutes of technology and polytechnics (ITPs) and private training establishments (PTEs) it's 25 to 34 years.

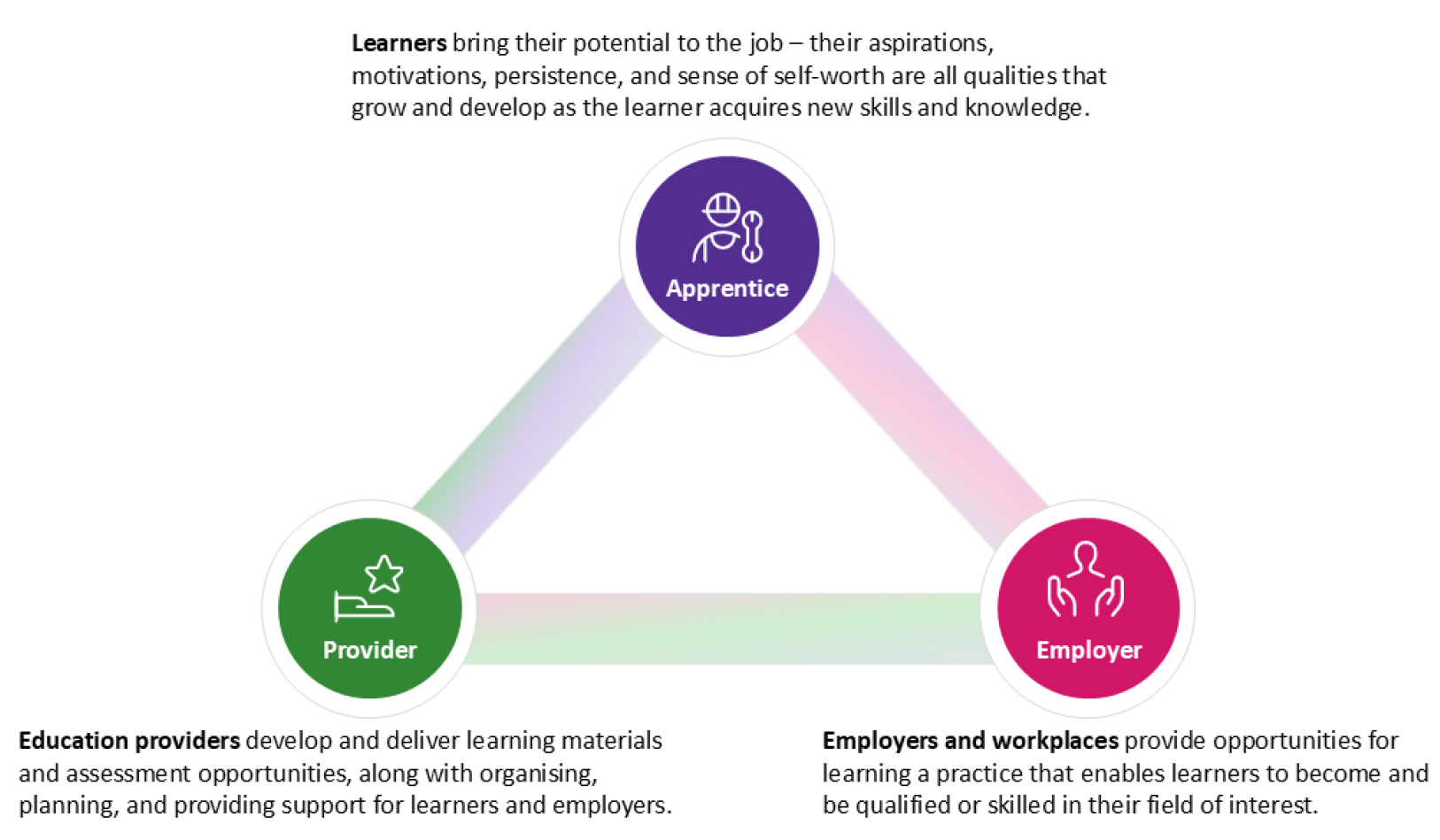

(Fig 4 from our report for ConCOVE, adapted from Anne Alkema’s

“Vocational Workplace learning: Who is in the driver’s seat?”)

Apprentices need consistent pastoral care and support for their wellbeing

Our research highlighted the fact that not all barriers to completion are financial. Apprentices often struggle with travel, with work-study balance, and with obligations to family and whānau.

Effective pastoral care can help resolve those kinds of issues for apprentices and support them to transition into new roles, particularly when they don’t have much work experience or have complex needs, such as housing, learning, or mental-health needs.

However, apprentices are both students and employees, and that creates ambiguity about who’s responsible and accountable for their wellbeing. Is it the education providers or the employers? Or is it both? That ambiguity can lead to inconsistencies and gaps in pastoral support.

The quality of training across employers is inconsistent

The barriers that apprentices face aren’t just about meeting the bills or juggling the demands of the apprenticeship with the rest of their lives. Another common reason we heard for apprentices not finishing was the quality of the training they got.

Quality can particularly be a problem when apprentices are supervised by individuals without formal training as education providers. Many employers, especially smaller businesses, don’t have the resources or knowledge needed to provide comprehensive training and support.

There’s an opportunity here for initiatives to develop employers’ skills as trainers and educators. This needs to be coupled with clearer mechanisms for employers to be accountable for the quality of the training they provide.

The set of support programmes are fragmented, and it’s hard to navigate the system

Currently, two core programmes provide apprenticeship support, and nine other programmes offer incentives for people to develop skills and get into jobs. Many of these programmes target similar challenges and overlap in their approach.

Information about support programmes and initiatives is spread across numerous websites and organisations, making it hard for apprentices and employers to identify information that’s authoritative. Many apprentices in fact rely on personal networks to both enter and navigate the training system, but that’s only going to work for the few who happen to have the right connections. It means potential apprentices miss out because they don’t know someone who can host them.

Many other countries have dedicated websites or portals that include all relevant apprenticeship information and also match up apprentices with employers.

The changes we recommended

The support system needs a clear shared vision

Our first set of recommendations addressed the fragmented nature of the support system. There needs to be a clearer collective vision for apprenticeships, with defined roles, responsibilities, and goals for everyone who participates in the system – this includes government, industry bodies, employers, training providers, and the apprentices themselves.

This should include a shared understanding of what’s good pastoral care for apprentices. Again, the roles and responsibilities here need to be explicitly spelt out, and the processes and the expected results need to be clear.

Pastoral care could be more effective if it were streamlined through a single point of contact, whether this is the training provider or someone else. This would remove the current ambiguities and gaps and would allow trusted relationships to develop over time. Funding also needs to be flexible enough to allow for tailored support for those who need it.

We also recommended consolidating all the current information resources in one place, in a dedicated portal or website, to help apprentices and others in the system to be more aware of available support. This is consistent with the general theme of a complex system that is difficult for both employers and apprentices to navigate.

Employers need to be supported to be better educators

Our second set of recommendations was aimed at supporting employers to be better trainers and educators.

We recommended formalising employer training programmes, clarifying the role of government in supporting employers to develop stronger capabilities, and exploring whether government’s current investment in employer training is adequate for the outcomes it wants to achieve.

At the same time, there also need to be appropriate accountability mechanisms for employers – potentially linked to financial incentives – to ensure the training they provide is high-quality.

We also recommended investing in research to get a better understanding of the gaps in employers’ capabilities as educators and the different barriers and challenges here.

To create a more effective apprenticeship system, employers, industry, and government need to work in partnership and with a consistent direction. This partnership requires well-considered investments and clearly defined roles so that each party can contribute effectively.

By addressing these challenges systematically, we can create an apprenticeship system that better serves learners, employers, and the wider economy, ensuring Aotearoa New Zealand has the skilled workforce our construction and infrastructure sector needs for a healthy future.

The full report prepared for ConCOVE by EeMun Chen, Natalie James, and Ben Craven from MartinJenkins is available on the ConCOVE website.