Local councils are now beginning to establish their new arrangements for delivering water services, and their success will depend to a large extent on how well they manage the workforce dimensions of the change process. Sarah Baddeley and Jessie Larsen explore this human side of implementing Local Water Done Well.

Jessie was previously the Workforce Change Lead at the National Transition Unit (Three Waters Reform) and Sarah has led transformation processes in the utilities sector.

The Local Water Done Well reforms involve one of the most significant workforce transitions in the history of New Zealand's local government. Estimates for the size of the workforce in this sector vary, but the Department of Internal Affairs has recently estimated it as needing to be more than 9,000 over the next 10 years. But what’s clear is that kaimahi across 67 councils will face some sort of change by June 2028.

The human and workforce dimensions are just as central to doing local water well as other core issues for councils like financial sustainability. Our experience working with councils and other organisations through major transitions has taught us that those that prioritise workforce planning from the outset are much more likely to maintain service continuity and achieve their transformation objectives.

Workforce transition planning needs to start now

As councils set their roadmap, they face a pressing set of complex decisions: What delivery model fits our available skills today and our pipeline tomorrow? How will we hold on to scarce expertise through uncertainty and fierce competition for talent? How will the changes we need to make align with individual and collective agreements? For those moving into joint water services organisations, how will staff from multiple councils move into their new teams equitably and fairly?

These questions require immediate attention from councils, even as they are just beginning to develop their implementation roadmaps. This includes not just councils setting up new water organisations, but also those that have decided to keep water services in-house.

In our work supporting councils we are also seeing in house units under-estimating two impacts: first, financial ring fencing, which changes overhead recovery and reporting; and second, additional regulatory responsibilities, which increase councils’ compliance workload and their capability needs. While those impacts may not be felt this financial year, they need to be planned for today.

Understanding your starting point: The current water services workforce

New Zealand’s water services workforce is far more diverse than many realise. Beyond the engineers and operators who keep treatment plants running, it encompasses dozens of specialised roles across field services, customer service, regulatory compliance, asset management, and digital systems. Each role carries unique knowledge, often built up over decades of local experience.

Mapping the current state of your workforce

Before councils can plan their workforce transition, they need a comprehensive understanding of who’s doing what currently. This isn't just about organisational charts – it's about understanding the intricate web of relationships, knowledge flows, and informal networks that keep water services functioning. It includes critical supply chains and the extended workforce.

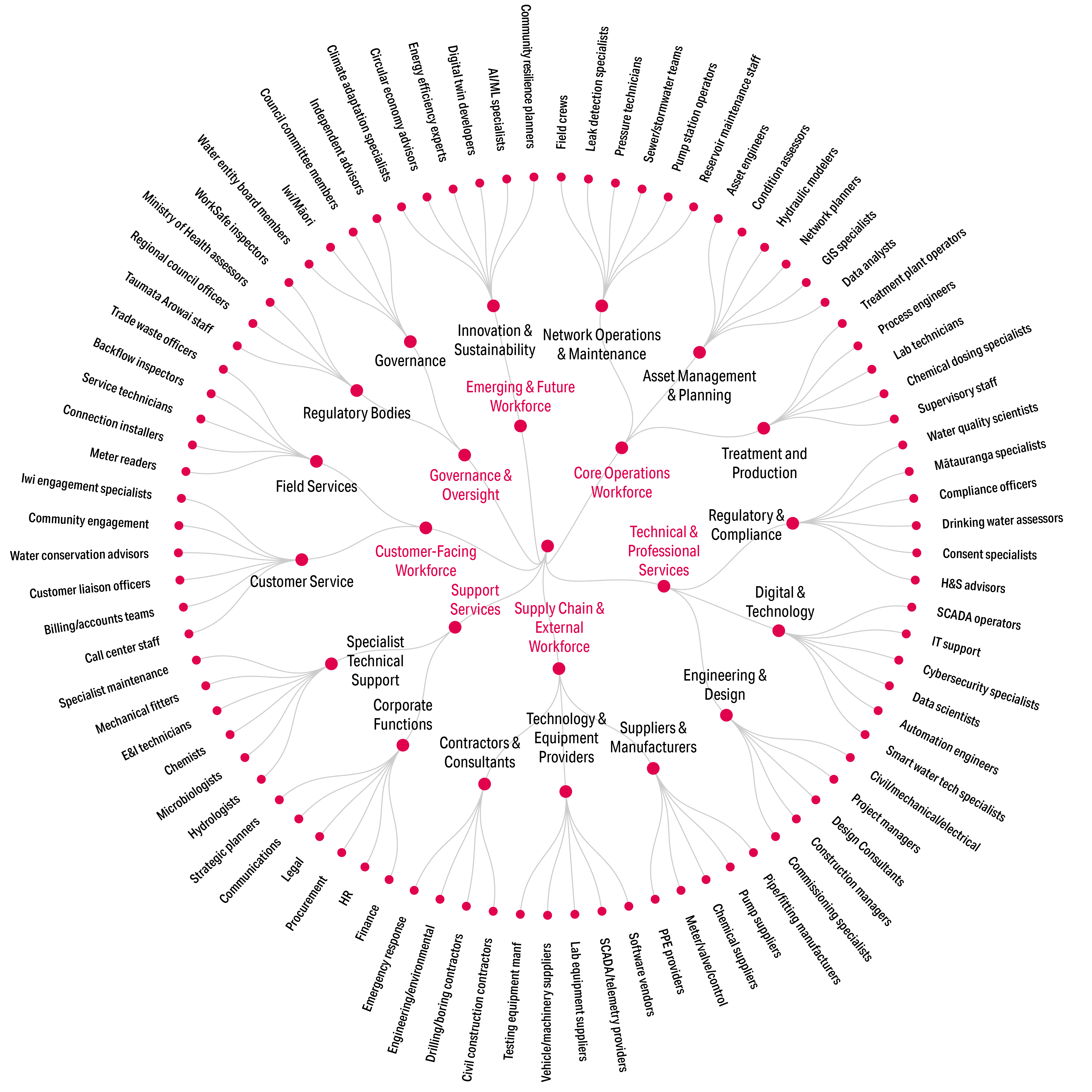

At MartinJenkins we use a workforce mapping framework that identifies over 60 distinct role types across the water services value chain, extending beyond councils into suppliers and over to regulators. From meter readers with intimate knowledge of local infrastructure quirks, to laboratory technicians who understand seasonal variations in water quality, each role contributes essential expertise.

Many councils are discovering that their water services workforce extends well beyond those formally designated as their three waters team, that it includes critical functions embedded in IT, finance, customer service, and other corporate areas.

The comprehensive workforce mapping framework we use at MartinJenkins

The geographical distribution of these roles adds another layer of complexity in the case of transitioning to a multi-council water services organisation. Field crews may be based hours from main offices, contractors may outnumber direct employees, and specialist expertise might be shared across multiple councils through informal arrangements. Understanding these arrangements is essential for planning transitions that don't inadvertently break critical service delivery chains.

Five integration pathways – and their workforce implications

Beyond the high-level choice of delivery model, councils have to work out the practical business of integrating their workforces into new structures. Our analysis of emerging approaches across New Zealand reveals five distinct integration pathways, each with specific workforce implications.

1. A lead host

In this approach, a larger council hosts the water services entity and gradually absorbs functions from smaller partner councils. This model works well when there's a clear capability leader with established systems and processes.

The model offers immediate stability for the host council’s staff, but it may potentially create anxiety for employees from smaller councils, who may feel like junior partners. Success requires deliberate culture-building to create a unified team rather than a hierarchy that depends on former employers.

2. Taking the best from each partner

This integration model cherry-picks the strongest capabilities from each participating council – perhaps one council's asset management excellence, another's customer service systems, and a third's field operations.

While this creates operational excellence, it presents significant workforce challenges. Staff may find their roles fundamentally changed as "best practice" from another council is adopted, which means giving a lot of attention to change management and training.

Success requires clear communication about the selection criteria for the capabilities, and genuine recognition of each council's contributions to maintain morale.

3. Transformation

Some councils are using the transition as an opportunity to completely reimagine how they deliver water services, moving quickly to an entirely new operating model.

This clean-slate approach can be exciting for staff who embrace change but deeply unsettling for those who value stability. It typically requires significant investment in change management, retraining, and probably some external recruitment to fill capability gaps.

The transformation model often sees the highest initial turnover, but it can ultimately create the most innovative workforce culture and enable the new organisation to deliver some of the wider benefits to customers and ratepayers sooner.

4. Preservation

At the opposite end of the spectrum, some councils are maintaining distinct operational units within a shared governance structure, at least initially. This minimises the immediate disruption and can be particularly effective for councils with strong existing performance.

However, it risks creating ongoing silos and may limit the efficiency gains that reform aims to achieve. Workforce integration in this model tends to happen gradually through natural attrition and shared projects, rather than through structural change.

5. Phased integration

Perhaps the most pragmatic approach involves starting with one council or function and progressively integrating others over time. This allows for learning and adjusting, and so reduces the risk of system-wide failure. For the workforce, it creates a rolling transition where some staff have certainty while others remain in limbo. Managing the different stages of integration simultaneously requires sophisticated change management and clear communication around milestones.

Different pathways reflect different priorities

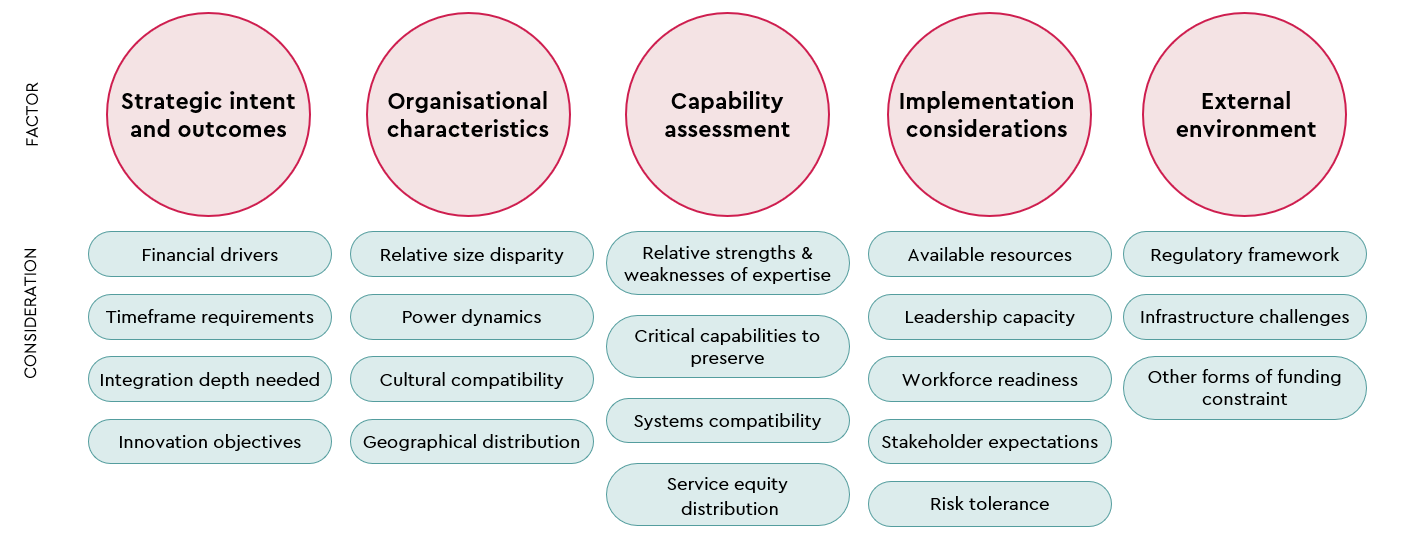

Each of those pathways reflects different priorities: speed or stability, innovation or preservation, efficiency or local identity. The choice should fit with the councils' collective risk appetite, change readiness, and workforce capability.

Importantly, councils can combine elements from different models – perhaps using a lead host for corporate services while transforming operational delivery or preserving some functions while rapidly integrating others.

Key risks and unintended consequences

Our analysis of the workforce impacts of Local Water Done Well reveals three categories of immediate impacts that councils need to actively manage. These extend far beyond just water services staff.

Loss of capability

Any change period can create transition-related risks to your capability that you will need to identify and actively manage.

- Flight of expertise towards more certainty – This happens when experienced professionals, particularly those approaching retirement, choose to leave rather than deal with organisational change. For example, we have already seen some of the early movers headhunt staff from those councils who have been slower to get going. We also need to be mindful of the drawcard of Australian job opportunities for those seeking stability and higher salaries.

- Evaporation of institutional knowledge happens when long-serving staff who hold critical undocumented knowledge depart before transfer mechanisms are in place. The classic case is where a council discovers that their most experienced operator was the only person who knew how to manage their treatment plant during specific weather events – knowledge gained over 30 years that existed nowhere in written form.

- Talent poaching – The competition will intensify as councils across the country simultaneously seek the same scarce expertise. Smaller and rural councils are particularly vulnerable, with in-house units unable to match the salaries and career opportunities offered by larger, dedicated water services organisations.

Resource gaps and disrupted support functions

When water services separate from councils, they take with them not just a water services team but also a proportion of corporate support. This creates two parallel challenges:

- Stranded overhead costs burden the remaining council operations. Finance teams sized for a larger organisation, IT systems with fewer users to share costs, and corporate functions that lose economies of scale all contribute to a financial squeeze on non-water services.

- Right-sizing your support functions becomes critical for both the council and the new water organisations. The new organisation needs sufficient corporate capability from Day 1, while the council must restructure its support functions for a smaller operational footprint.

Financial implications beyond the obvious

The workforce transition creates financial impacts that extend well beyond direct employment costs. These include:

- redundancy provisions that could be triggered even for staff whose roles continue, if their employment technically transfers

- knowledge transfer costs, including documentation, training, and parallel running arrangements

- recruitment and retention premiums in a highly competitive market

- temporary capability supplements through contractors and consultants during the transition

- investments in culture development to build cohesive new organisations from disparate workforce groups, and

- investments in change management to understand and manage the impacts on people, processes, and technology and ensure a seamless transition of services.

To manage workforce impacts and risks, here’s what you need to get right from the start

Success in your workforce transition and in managing those workforce impacts and risks requires councils to act decisively on six critical fronts, even while you’re still developing the broader organisational structures.

1. Early and transparent communication

Uncertainty is the enemy of workforce stability. From the outset, councils must commit to regular, honest communication with all affected staff – not just those in water services roles. This means acknowledging what you don’t yet know, providing realistic timelines, and creating multiple channels for leaders and staff to talk to each other.

Effective councils are establishing dedicated communication channels for the transition – including weekly briefings, dedicated intranet sites, and regular Q&A sessions. They're also training managers at all levels to have difficult conversations about uncertainty while maintaining the cohesion of their teams and a focus on service delivery.

2. Genuine consultation with unions and workers

The major water sector unions – PSA, First Union, E tū, and the Amalgamated Workers Union – have developed sophisticated approaches to water reform transitions. Engaging early on with union representatives (including in-house unions) will be important for your transition.

This isn't just about compliance – it's about accessing valuable insights into what your workforce is concerned about and co-designing solutions that work for everyone.

Leading councils are going beyond minimum consultation requirements here. They’re establishing joint transition committees, involving union representatives in organisational design processes, and developing employment protection agreements that go above and beyond the statutory minimums.

3. Strategies for retaining skills

With every council competing for the same scarce expertise, retention strategies need to be immediate and provide a compelling employee proposition.

This goes beyond financial incentives to include:

- clarity about career pathways, showing how roles will evolve in new structures

- investments in learning and development that benefit employees regardless of future organisational arrangements

- retention agreements that balance security for critical roles with flexibility for organisational change

- accelerated succession planning, to develop internal talent pipelines.

4. Fair and equitable processes

How your council manages this workforce transition will define your employment brand for years to come. It will depend on fair processes that address individual circumstances compassionately, ensure no group is disadvantaged, and maintain transparent decision-making criteria.

This is essential not just for legal compliance, but also for your organisational reputation.

5. Supporting your people’s wellbeing

Organisational change takes a psychological toll, even for staff whose job security is assured. Progressive councils are providing Employee Assistance Programmes, resilience training, and dedicated support for managers dealing with team members’ anxiety. Regular “pulse” surveys will help you identify emerging wellbeing issues before they affect service delivery or safety.

6. Capturing and transferring knowledge

With institutional knowledge at risk, you will need to start systematically capturing it immediately. This should include mapping your contractor and supplier relationships to ensure continuity of service arrangements, and documenting key processes and systems.

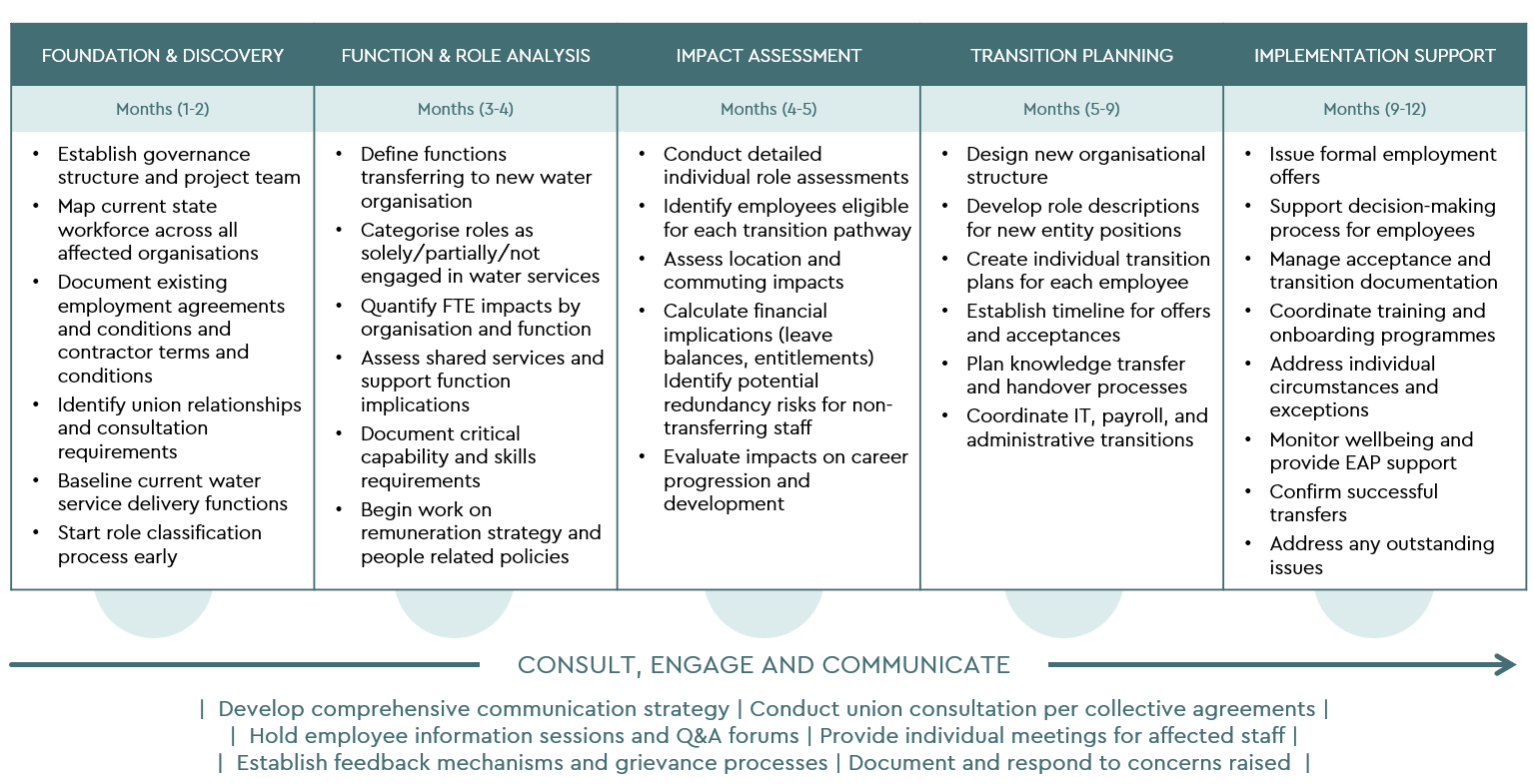

Your workforce transition roadmap: 12 months to get to Day 1

Although each council's journey will be unique, successful workforce transitions typically follow a structured pathway. The table below sets out a 12-month programme of preparatory work that you may find useful as a guide.

Beyond compliance: Building water services careers for the future

Legislation provides minimum protections for employees, but councils can also use this transition to address longstanding workforce challenges in the water sector.

This includes developing clear career pathways that attract younger workers, creating apprenticeship and graduate programmes that build sustainable talent pipelines, and establishing remuneration frameworks that recognise the critical importance of water services while maintaining fairness across the local-government sector.

The new water services organisations can become employers of choice by offering professional development opportunities, embracing diversity and inclusion to tap into underutilised talent pools, and building cultures of innovation and continuous improvement.

Moving forward with confidence

The workforce dimension of Local Water Done Well presents both the greatest risk and the greatest opportunity for councils. The clock is ticking, but councils shouldn't let urgency drive hasty decisions. The workforce transitions being planned today will determine whether New Zealand's water services have the human capability to meet community needs for decades to come.

For councils at the beginning of this journey, three actions are critical right now:

- establish your transition programme structure, with dedicated expertise in workforce questions

- begin comprehensive workforce mapping across all affected areas, and

- start the conversation with your people – they are, after all, the ones who’ll make this transition succeed.

The path ahead is complex, but councils that establish clear transition processes, communicate transparently with affected staff, and invest in retaining knowledge and developing capability can travel it successfully while maintaining the trust of both their workforce and their communities.