Allana Coulon, our Managing Partner, explores the main labour market changes expected through to 2030 and what they mean for HR professionals planning for future workforce needs. This article was first published in the Summer 2025/26 issue of Human resources magazine.

The jobs and the people in New Zealand’s labour market are changing. Over the next five years, demographic shifts, migration patterns, and technological advances (particularly AI) will reshape workforce characteristics, job design, and skill needs across the economy.

Demand for talent will outstrip our ageing, slower-growing workforce

Unemployment climbed to 5.2% in June 2025, but certain sectors and regions still face a tight labour supply, and skilled workers are still in high demand. In effect, we have a two-speed labour market with some sectors declining and laying off workers, while others continue to have skill shortages.

Longer term, it’s expected unemployment will plateau or rise slightly in 2026 then fall back by 2030, amid persistent talent constraints driven by structural factors such as ageing and skill mismatches.

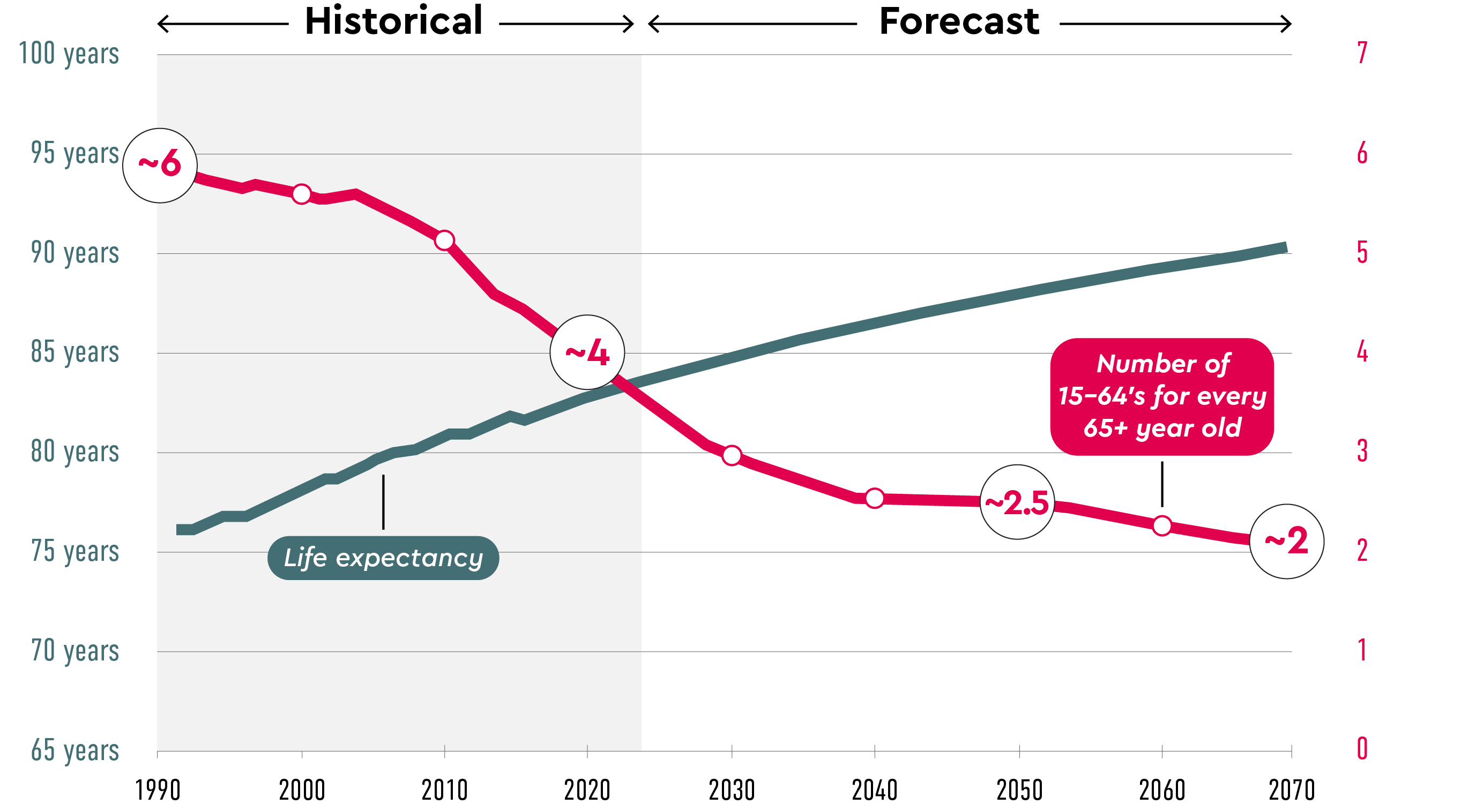

New Zealand’s working-age population is getting decidedly older. The median age is projected to rise from 38.9 years in 2025 to 43.7 by 2050. One in six Kiwis is now aged 65 or above, and by the mid-2030s it will be one in five. The number of people retiring each year is increasing, while the number of young people entering the workforce is not keeping pace. In the early 2000s, labour force growth averaged around 500,000 per decade, but it has now slowed to around 320,000 per decade and is expected to keep declining.

Life expectancy is increasing, while the proportion of 15–64 year olds to over-65s is declining

This means the pool of available workers is growing more slowly than the economy’s demand for skills. For HR leaders, this shift requires a fundamental rethink of how we source and sustain talent.

HR leaders can no longer assume migration will reliably fill our workforce gaps

The HR response must be multi-pronged because we can no longer assume that the traditional ways of overcoming labour shortages will continue to serve us in the future.

Historically, migration has been New Zealand’s emergency reserve to fill skill gaps. Over the next five years, migration will continue to be crucial, but it’s also proving to be highly volatile and competitive, and we can no longer assume traditional ways to overcome labour shortages will continue to work.

In 2023, New Zealand experienced an unprecedented surge in migration. As borders reopened post-pandemic, we hit a record net 12-month migration gain of 134,000 people in the year to October 2023. Suddenly critical roles in IT, engineering, and health care were easier to fill. But by late 2024 the situation had flipped: a record 127,800 people left New Zealand in the year to November 2024 (mostly Kiwis heading to Australia), and arrivals slowed. The net gain in those 12 months was just 30,600 – less than a quarter of the net inflow in the year to November 2023.

That whiplash shock reminds us that we can’t take migration for granted. Global competition for skills is heating up. Australia and Canada, for example, are aggressively courting skilled migrants, and many New Zealanders are lured offshore by higher wages or lifestyle factors. Geopolitical instability (from pandemics to conflicts) can disrupt mobility unexpectedly. Economic cycles matter too: if our economy softens while others boom, we get outflows (as we’ve just seen with the pull of Australia).

We need to control what we can

While migration will still be a vital part of the solution, we need to be proactive about controlling what we can.

So hold tight to what you’ve got – focus on succession plans, retaining skilled workers, and developing local talent. Remember too to keep driving performance: uncertainty can cause the disengaged to stay put, which can be a drag on organisational performance if not actively managed.

At the same time, be deliberate about how you compete globally because the competition is likely to only get fiercer. Consider how attractive your organisation and New Zealand are to offshore talent and how well you support your overseas hires in adapting to life here.

Artificially augmented work

Over the past year, generative AI has spread like wildfire across New Zealand workplaces and is beginning to irreversibly change how we do our jobs. The recent Datacom State of AI report revealed that 88% of New Zealand organisations are using AI and reporting positive effects for their operations.

So far, AI seems to be augmenting, not replacing, our current workforce, with 89% reporting productivity gains, according to Datacom’s report. It’s allowing experienced workers to shift away from more mundane, repetitive tasks, and organisations to redeploy people to tasks that AI can’t do as well.

In some instances, this is a natural and positive transition for workers; in others, upskilling or retraining is required to adapt to the change in job focus.

I talked recently with Josh Robb, a co-founder of Tend Health, New Zealand’s leading digi-physical healthcare provider. Tend’s goal is to combine AI and human clinical expertise to make primary health care easier to access, safer, more equitable, and cheaper. Josh described the “Aha!” moment new clinical practitioners have when they realise the benefits of having AI supporting administrative tasks, allowing them to focus on patient care, communication, and relationships. It’s also allowing clinics to better match tasks to the right clinician and use scarce resources more effectively, helping more patients to receive the care they need.

For HR and business leaders, building a hybrid artificial–human workforce requires the careful redesign of jobs and a clear assessment of future skills requirements. Already we’re seeing a growing trend towards skills-based hiring over role-based hiring, because the ability and willingness to adapt are becoming more important than prior experience or education alone.

Upskilling the 80% already working for us

The fastest way to build the future workforce is to invest in our current workforce, because 80% of the workforce of 2030 are already on our payrolls.

If we want to compete by retaining skilled workers and optimising the mix of people and technology, we have to stop treating L&D as a nice-to-have and something to do in fair economic weather. Transitioning our workforce towards future skills and ways of working needs to be baked into our culture, budgets, and strategic plans. It needs to be the business of all leaders, and not just HR business. HR can support this by working with organisational leaders to set the tone. Consider the mix of signals, incentives, and encouragement that will work for your people.

The next generation – don’t cut the graduate pipeline

As HR leaders, we’re custodians of our organisation’s future talent pipeline. Ensuring young people transition successfully from education into the workforce is going to be vital over the next five years. But evidence shows some firms, notably technology and professional services, are slowing or freezing their recruiting of graduates, rationalising that “AI can do the junior work”. But if we drastically cut their opportunities now, what does it mean for our future talent pipeline?

Internationally, the idea of an AI glass floor is being discussed. In the US, the unemployment rate for college graduates climbed to about 6% in early 2025, which is, unusually, higher than the overall national rate. It was observed that the sharpest job losses were in sectors like professional services, where AI is being adopted the most rapidly. The inference is that AI may be impacting on jobs for graduates.

Here in New Zealand, the Not in Employment, Education or Training (NEET) rate for 15 to 25-year-olds was 12.9% in June 2025, compared with 5.2% overall. A young unemployed worker recently told Radio NZ: “The majority of younger people are actually very, very, very eager to work. It's just a matter of there are very few opportunities for that now…” Young workers are always hit hardest in recessions, and that high NEET figure is probably mostly due to the general downturn. But I’m finding a concerning trend cropping up in my conversations with organisational leaders, suggesting that AI may be exacerbating the barriers faced by our young jobseekers.

Today’s graduates are tomorrow’s specialists and leaders. If we throttle the intake now, we’ll feel the succession pinch five to 10 years from now. Courage and a sense of longer-term social responsibility are needed.

Making the future of work fair

Many organisations are already considering how AI is likely to affect different jobs in the future and the workers doing them.

Lower-paid and less-skilled workers typically feel the brunt of job displacement in technological shifts. There have been warnings that in some occupations Māori and Pacific Peoples could be disproportionately displaced by AI, and also that in its impact on women’s participation in the labour market, AI could potentially deal as big a blow as the mechanisation of the textile industry in the late 18th century. But it's in no-one’s interest to leave those workers stranded, and so looking for opportunities to retrain people into new roles is going to be central.

Considering equity and inclusion in how we adapt to demographic, technological, and economic shifts is a social imperative. But it’s also, frankly, a business advantage. Leaders need to play the long game here, because all signs are that the labour market will tighten and the global competition for skills will increase. Lifting our eyes to the horizon now and thinking about how we will help our current workforce adapt to new roles is a savvy business strategy.